The Arab world has a rich satirical tradition that has appeared in numerous forms throughout its history, ranging from satirical al-hija1 poetry of the pre-Islamic era to the satirical newspaper Abou Naddara Zarqa, published in late nineteenth-century Cairo by the Jewish Egyptian polyglot Yaqub Sanu. Throughout the twentieth century, satire flourished in theatrical form and the political cartoons of Ali Ferzat and Naji al-Ali as well as in the widespread circulation and popularity of political jokes around the Arab world, as recorded by Khalid Kishtainy in his 1986 work Arab Political Humor. The rapid growth in Internet usage in the region in the early twenty-first century has only served to increase the ease and speed with which these images, articles, and jokes are shared between friends and family.

The ability to make people laugh has, of course, always been central to these forms’ lasting popularity. However, they have also frequently been used as a means to discuss serious political issues, to critique societal and religious norms, and to express dissent and protest. Satire in the Arab world has frequently been directed not only against local rulers and other repressive elites, but also—especially in the modern period—against Orientalist projections from outside of the region that have so often denigrated and exoticized Arabs and Arab culture.

An article that was published in the Lebanese satirical newspaper, Al-Sahafi Al-Ta’ih [The Errant Journalist] in July 1936 offers a perfect historical example of humor and subversive political commentary being combined in this manner. The article, preserved in the India Office Records held at the British Library in London, has come to light recently as these records are currently being digitized. This ongoing digitization project, a partnership between the British Library and the Qatar Foundation, has seen the creation of a bilingual (English and Arabic) open access online portal containing high-quality images of these records, full catalogue information, and contextual essays about their content.

The controversy that the Al-Sahafi Al-Ta’ih article caused and the way in which this episode was subsequently dealt with by the British authorities serves to illustrate the nature and extent of Britain’s colonial dominance over Bahrain at this time. It also provides evidence of the long-standing popularity of satire in the Arab world and offers a fascinating glimpse into the type of political satire that was popular in 1930s Beirut and the critical imagery that it used.

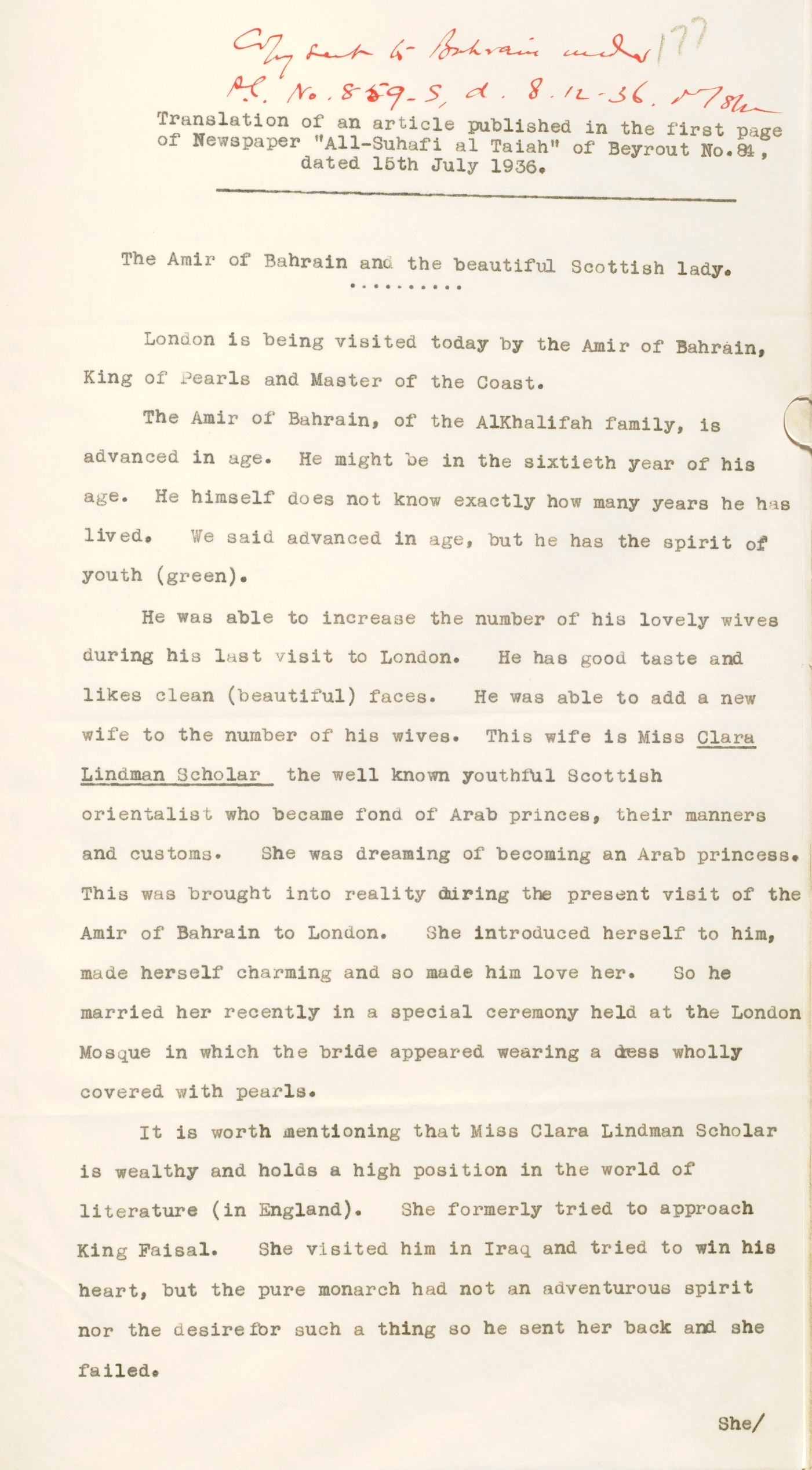

In June 1936, the ruler of Bahrain, Shaykh Hamad Bin Isa Al Khalifa, made an official state visit to Britain.2 Following the trip, Al-Sahafi Al-Ta’ih published an article in July 1936 on its front page entitled “The Amir of Bahrain and the Beautiful Scottish Lady.” According to an English translation of the article preserved in the records of the British Political Residency in the Persian Gulf, the original article described in humorous detail a chance meeting between Shaykh Hamad and a certain Miss Clara Lindman. The meeting is said to have culminated in a specially arranged wedding held at the London Mosque at which “the bride appeared wearing a dress wholly covered with pearls.” The article described Lindman as a “well known, youthful Scottish orientalist” who had become fond of Arab princes, “their manners and their customs,” and was “dreaming of becoming an Arab princess.” The article even claimed that prior to meeting Shaykh Hamad, Lindman had travelled to Iraq in an attempt to win the heart of King Faisal, but the “pure monarch had not an adventurous spirit nor the desire for such a thing” and so Lindman had failed in her attempt. The piece explains that although Shaykh Hamad was “advanced in age,” and did not know himself how old he was, he had the “spirit of youth” and so increased the number of his “lovely wives.” Shaykh Hamad is described as “King of Pearls and Master of the Coast” and as having “good taste” and liking “clean (beautiful) faces.”

Image 1: First page of an English translation of the article that was published on the front page of Al Sahafi Al-Ta’ih No. 8, 15 July 1936. Reference: IOR/R/15/1/363, f 177.

Al-Sahafi Al-Ta’ih was established in 1922 by Lebanese journalist Alexandre Riashi. By 1936, through its biting political satire and risqué humor, the paper had become popular and acquired a significant readership in Beirut. The tone of the article shows a distinct awareness of the well-established, Orientalist trope of the over-sexualized and lustful Arab man who apparently posed a threat to the purity of European women. It also humorously mocks the exoticized desire for the “other” through the character of Lindman, an “orientalist” with her heart set on wooing an “Arab prince”. Interestingly, this cliché is turned on its head as the oriental “other” is usually gendered female while the gaze of the occidental Orientalist is assumed to be male. The representation of Shaykh Hamad as enormously wealthy, unsophisticated (he is ignorant of his own age), ostentatious in taste (“a dress wholly covered with pearls”), and having a proclivity for acquiring wives is one that remains recognizable today in mainstream media depictions of the Gulf but was already prevalent as early as the 1930s. For example, in January 1935, the British newspapers The Daily Express and The People published articles about the ruler of Qatar, Shaykh Abdullah bin Jassim Al Thani, that gave “Arabian nights accounts of the eighty-odd members of his beautiful harem, his ‘piles of pearls,’ the breath taking qualities of his court and his romantic country complete with four thousand slaves.” As observed by Rosemarie Said Zahlan, in the case of Qatar, “nothing could have been further from reality.”3

It is debateable whether Riashi intended his representation of Shaykh Hamad in the article as a pastiche of stereotypical Western portrayals such as these or that he had in fact internalized some of them and adopted a superior, patronizing attitude towards the Gulf himself. This form of “internal Orientalism,” by which Arabs outside of the Gulf region believed pejorative stereotypes characterising the people of the region—in particular their rulers—as wealthy, ignorant, and uncivilized tribesmen remains prevalent today. Given the contempt with which the monarchs of the Gulf states were held by many within leftist and liberal-nationalist circles in Beirut at the time it is likely that it was Riashi’s primary intention to lampoon Hamad (and Gulf monarchs in general) rather than to critique their representation in the West. The article’s characterization of King Faisal of Iraq as “pure” hints at the more positive standing with which Iraq was held by many in these same circles. Faisal and his son King Ghazi (who succeeded his father in 1933) were respected by many as Arab nationalist leaders and Hashemite Iraq was an important state sponsor of Arab nationalism during this period. More broadly, although Iraq was also a monarchy—with its constitution and parliament—it was seen to be a liberal and progressive state, in contrast with the “backward” tribal chiefdoms of the Gulf.

Although Al-Sahafi Al-Ta’ih claimed to have picked up the report concerning Shaykh Hamad’s marriage from the Sunday Express, a British daily newspaper, given the article’s outlandish claims and overtly comical tone, it is not clear whether many of its readers would have believed the story to be true. It can be said with more confidence that when Riashi released the article, it is very unlikely he believed that Shaykh Hamad himself would read the article, but read it he did, and regardless of Riashi’s exact intentions, the shaykh was not amused.

The official British representative in Bahrain at this time was its Political Agent in the country, Percy Gordon Loch, but Britain also had an alternative, unofficial means of influence, a former British Army Officer named Charles Belgrave. In 1926, Belgrave was appointed as Shaykh Hamad’s advisor and although he was not officially a British government employee, he had been interviewed and recruited by British officials. By 1936, Belgrave had become a central figure whose influence in Bahrain arguably rivalled that of Shaykh Hamad himself.

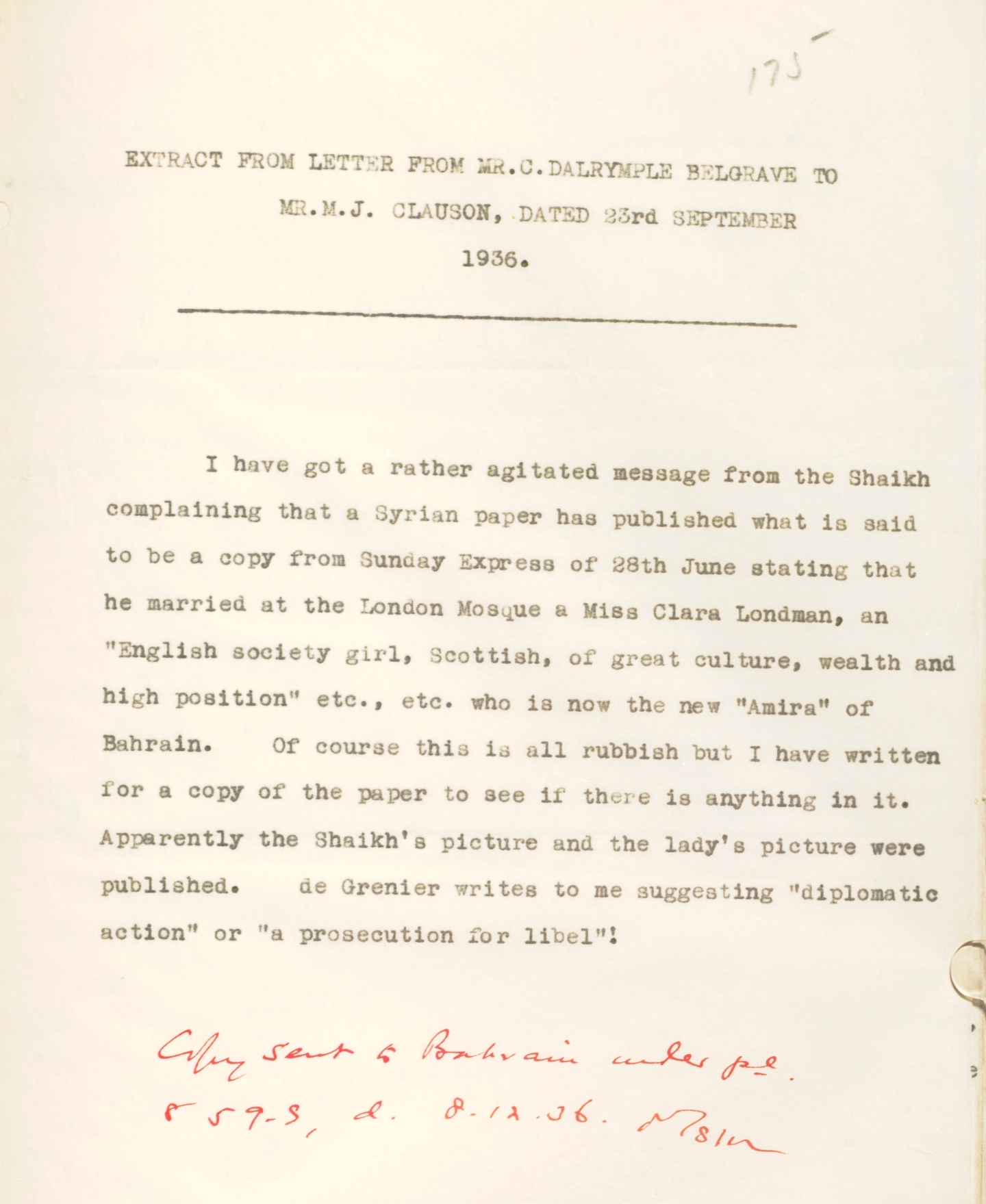

In September 1936, Belgrave wrote a letter to M.J. Caulson of the British Foreign Office informing him that he had just received an “agitated” message from Hamad regarding the article about him in Al-Sahafi Al-Ta’ih. According to Belgrave, Claude de Grenier, head of Bahrain’s customs department, was said to be outraged and calling for “diplomatic action” or a “prosecution for libel” in response. In further correspondence with Caulson, Belgrave confirmed that Hamad had indeed visited the London Mosque during his visit, but claimed that “he hardly had time to fall victim to Miss Clara Lindmand (sic)” and that contrary to the claims of the article in Al-Sahafi Al-Ta’ih, there had been no report in the Sunday Express on which the article could have been based. Belgrave then requested the Foreign Office’s assistance in soliciting an apology and correction from the paper. Hamad was said (by Belgrave) to be upset that “his name should be associated with that of a presumably non-Muslim lady whom he does not know.” Belgrave’s close relationship with Shaykh Hamad was essential to maintaining his prominent position, so his desire to placate him is unsurprising.

Image 2: Extract of Letter from Mr. C. Dalrymple Belgrave to Mr M.J. Clauson, 23 September 1936. Reference: IOR/R/15/1/363, f 175.

Although Bahrain was never formally a part of the British Empire, a series of treaties agreed between the British government and Al Khalifa in the nineteenth century had given Britain control over Bahrain’s foreign relations and formalized its dominant position in the country. The British considered Shaykh Hamad amenable to British interests and installed him as ruler in 1923 after they had forced his father Shaykh Isa Bin Ali Al Khalifa to abdicate. Therefore, maintaining a positive relationship with Shaykh Hamad served to buttress Britain’s hegemonic role in Bahrain and the Persian Gulf region more broadly. Accordingly, Foreign Office officials considered Shaykh Hamad’s concern with the Al-Sahafi Al-Ta’ih article a serious matter.

In correspondence from October 1936, T. V. Brenan, of the Foreign Office, reasoned that as the article was by then three months old, “it might do more harm than good to have a contradiction inserted even if it were possible to arrange this.” However, Brenan did agree to bring the matter to the notice of G. W. Furlonge, the British Consul-General in Beirut.

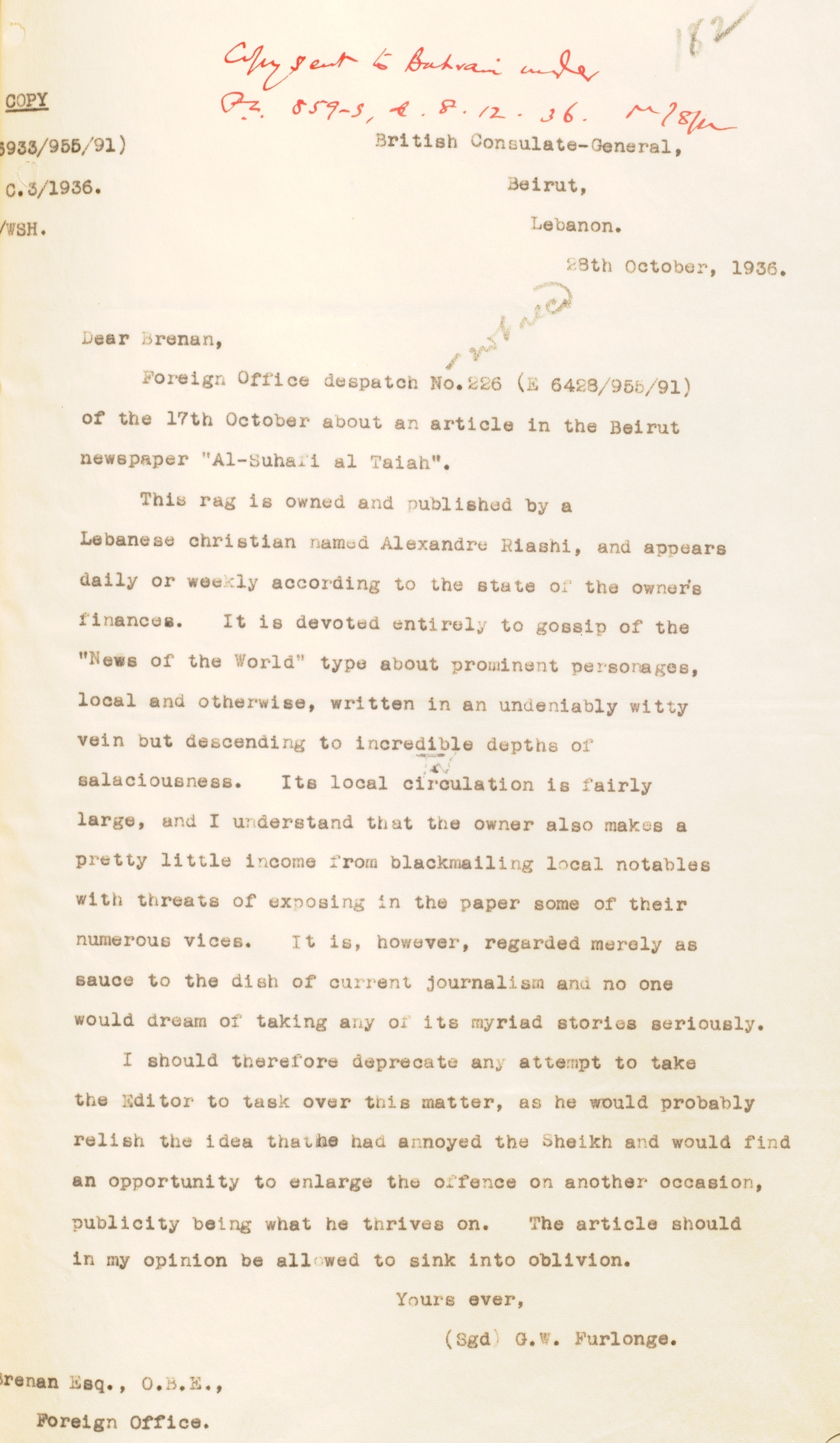

Furlonge responded to Brenan’s inquiry later that same month and his local knowledge proved invaluable in determining the appropriate response to the matter. Furlonge explained that Al-Sahafi Al-Ta’ih was a “rag” that was “devoted entirely to ‘News of the World’ type gossip” which although written in “an undeniably witty vein” descended to “incredible depths of salaciousness.” Furlonge even alleged that its owner, Riashi, supplemented his income from the paper by blackmailing local notables with threats of exposing some of their “numerous vices.” Crucially, Furlonge stated that “no one would dream of taking any of its myriad stories seriously” and strongly argued against any attempt to push for an apology or correction to be published, arguing that the editor would “relish the idea that he had annoyed the Sheikh and would find an opportunity to enlarge the offence on another occasion.” This interpretation supports the contention that it was Riashi’s primary intention to ridicule Hamad—as a representative of pro-British, “backward” monarchical rule in the Gulf—rather than to attack Western Orientalist representations of Arabs. Furlonge concluded his letter to Brenan with the advice that—in his opinion—the article should be allowed to “sink in to oblivion.”

The last item in the records that refers to this incident is a short message from the British Political Resident in the Persian Gulf4 to the Political Agent in Bahrain stating that he agreed that no further action should be taken concerning the article and that Belgrave should be informed accordingly. Hence, it appears that since Furlonge’s advice was heeded, Riashi never received the satisfaction of knowing about Shaykh Hamad’s anger, and the article had indeed sunk into oblivion, until now.

Image 3: Letter from G. W. Furlonge, British Consul General in Beirut to T. V. Brenan at the Foreign Office, 28 October 1936. Reference: IOR/R/15/1/363, f 182.

Britain’s dominant position in Bahrain is made clear by the fact that the final say in the matter lay with British officials and not Shaykh Hamad; the Foreign Office took the decision that no further steps should be taken and Belgrave delivered the news. Shaykh Hamad, ostensibly a sovereign ruler—despite his obvious desire to take some kind of action—was unable to act on his own accord. As the then British Political Agent in Bahrain Charles Geoffrey Prior observed in a remarkably frank letter from 1929, the notion that Bahrain was an independent state was nothing more than a “legal fiction.”5 Belgrave was to remain in Bahrain for another twenty years until 1957, when popular pressure forced him to leave and return to Britain. By this time he had become an extremely unpopular figure in the country and, as shown in this BBC archival clip from 1956, calls for him to leave the country were at the forefront of the demands of protestors at the time. However, Britain’s position in Bahrain was not dependent on Belgrave alone and it was to remain the dominant colonial power until Bahrain received its independence in 1971.

Al-Sahafi Al-Ta’ih constitutes a part of the deep-rooted and diverse tradition of satire in the Arab world, a tradition that despite the best efforts of government censors and security services throughout the region has flourished and continues to do so. Indeed, it seems that the intimidation and imprisonment (and worse) of satirists has merely provided additional motivation to like-minded individuals and, in turn, further enriched this tradition. The ongoing period of transformation, turbulence, and upheaval that the Arab world is witnessing is likely to ensure that there is no shortage of inspiration for the creation of scathing political satire in the months and years to come.

1 There is a sub-genre of hija called al hija al siyasi or political hija that dealt explicitly with more political themes. The genre’s most famous proponent is perhaps the eighth/ninth century poet Abu Nawas.

2 For more context on how these officials state visits were used by the British during this period, see this article.

3 Rosemarie Said Zahlan, The Creation of Qatar (London, 1979): 11.

4 This was the most senior British official in the region. Such was the holder of this post’s power that he was often referred to as رئيس الخليج [Chief of the Gulf] in Arabic.

5 British Library, London, `File 19/109 V (C 32) Bahrain Relations with other Foreign Powers`, IOR/R/15/1/322 f. 46.